Researchers have demonstrated a robot capable of sorting, manipulating, and identifying microscopic marine fossils. The new technology automates a tedious process that plays a key role in advancing our understanding of the world’s oceans and climate – both today and in the prehistoric past.

“The beauty of this technology is that it is made using relatively inexpensive off-the-shelf components, and we are making both the designs and the artificial intelligence software open source,” says Edgar Lobaton, co-author of a paper on the work and an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at North Carolina State University. “Our goal is to make this tool widely accessible, so that it can be used by as many researchers as possible to advance our understanding of oceans, biodiversity and climate.”

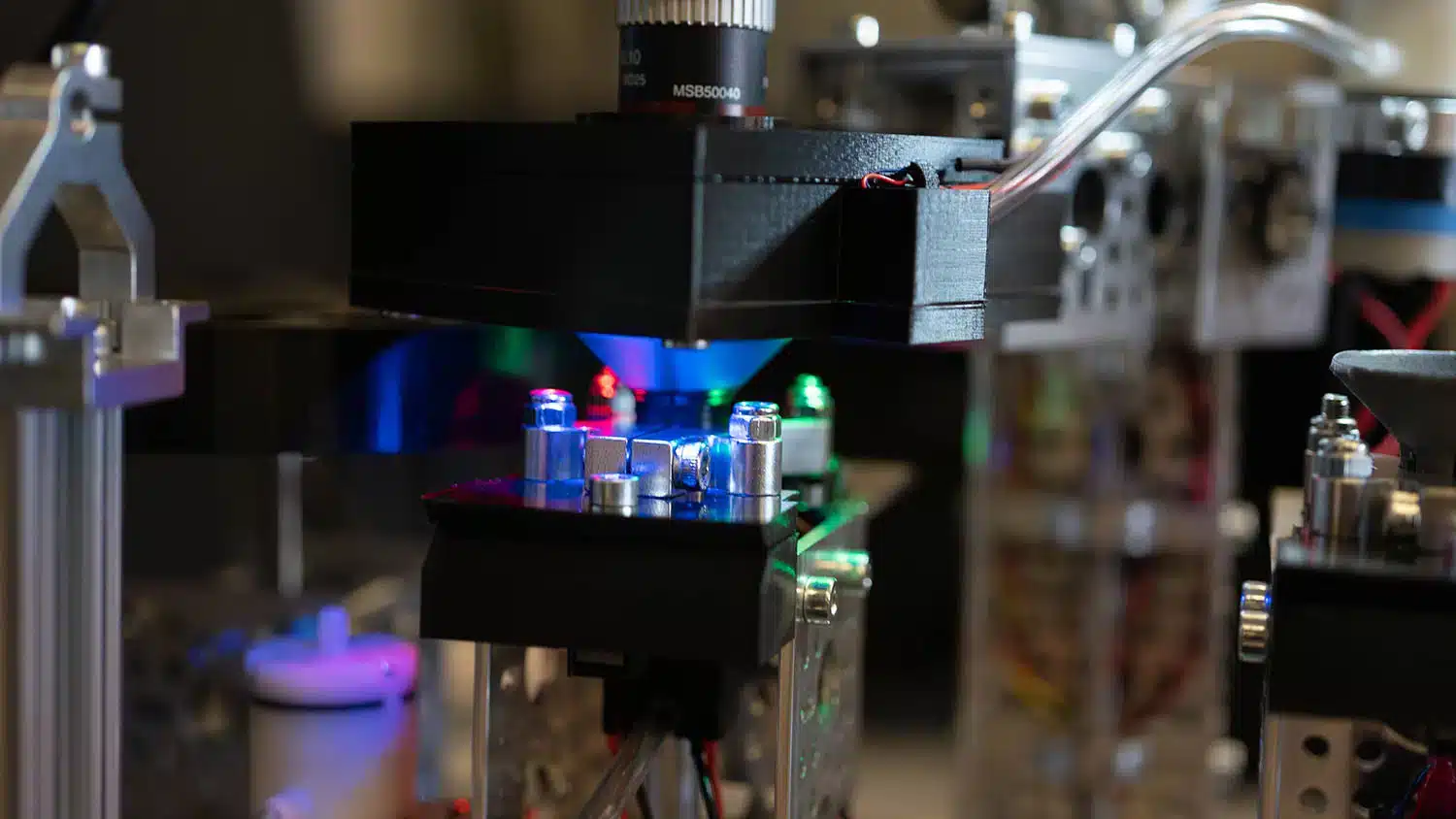

The technology, called Forabot, uses robotics and artificial intelligence to physically manipulate the remains of organisms called foraminifera, or forams, so that those remains can be isolated, imaged and identified.

Forams are protists, neither plant nor animal, and have been prevalent in our oceans for more than 100 million years. When forams die, they leave behind their tiny shells, most less than a millimeter wide. These shells give scientists insights into the characteristics of the oceans as they existed when the forams were alive. For example, different types of foram species thrive in different kinds of ocean environments, and chemical measurements can tell scientists about everything from the ocean’s chemistry to its temperature when the shell was being formed.

However, evaluating foram shells and fossils is both tedious and time consuming. Which is why a team of engineering and paleoceanography experts developed Forabot to automate the process.

“At this point, Forabot is capable of identifying six different types of foram, and processing 27 forams per hour – but it never gets bored and it never gets tired,” Lobaton says. “This is a proof-of-concept prototype, so we’ll be expanding the number of foram species it is able to identify. And we’re optimistic we’ll also be able to improve the number of forams it can process per hour.

“Also, at this point, the Forabot has an accuracy rate of 79% for identifying forams, which is better than most trained humans.”

“Once Forabot has been optimized, it will be a valuable piece of research equipment, allowing student ‘foram pickers’ to better spend their time learning more advanced skills,” says Tom Marchitto, co-author of the paper and a professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “By using community-sourced taxonomic knowledge to train the robot, we can also improve uniformity of foram identification across research groups.”

Here’s how Forabot works. First, users have to wash and sieve a sample of hundreds of forams. This leaves users with a pile of what looks like sand. The sample of forams is then placed into a container called the isolation tower. A needle at the bottom of the isolation tower then projects up through the sample, lifting a single foram up where it is removed from the tower via suction. The suction pulls the foram to a separate container called the imaging tower, which is equipped with an automated, high-resolution camera that captures multiple images of the foram. After the images are taken, the foram is again lifted by a needle until it can be picked up via suction and deposited in the relevant container in a sorting station.

“The idea is that our AI can use the images to identify what type of foram it is, and sort it accordingly,” Lobaton says.

“We’re publishing in an open source journal, and are including the blueprints and AI software in the supplementary materials to that paper,” Lobaton adds. “Hopefully, people will make use of it. The next step for us is to expand the types of forams the system can identify, and work on optimizing the operational speed.”

The paper, “Forabot: Automated Planktic Foraminifera Isolation and Imaging,” is published in the open-access journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. Corresponding author of the paper is Turner Richmond, a recent Ph.D. graduate from NC State. The paper was co-authored by Jeremy Cole, a Ph.D. graduate of NC State; and by Gabriella Dangler, an undergraduate at NC State.

The work was done with support from the National Science Foundation, under grant number 1829930.