Could he — would he — make it in a newly integrated college?

Could he — would he — do something that had never been done by an African-American student-athlete?

Durham native Irwin Holmes wasn’t sure. But his mother had no doubts.

“I go to this all-white college and I have no idea how I’m going to compete in this new environment,” Holmes says. “Is it really true that blacks aren’t as smart as whites, and I’m not going to do well? Or is it like my mom told me, that I’m as good as anybody?

“When I got there, I found out my mom was more right than the rest of the world.”

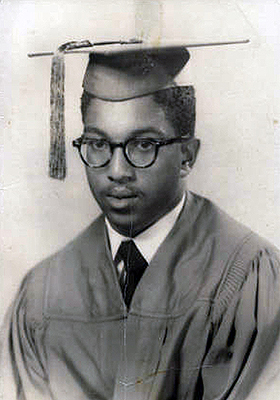

In the fall of 1956 Holmes and three other pioneering students became NC State’s first African-American undergraduates, changing the once all-white face of the institution when they enrolled in what was then called the School of Engineering. In their time on campus, the students broke one barrier after another by participating in the tennis, soccer, and indoor track and field teams, and in the marching band.

in electrical engineering in 1960.

After completing a distinguished academic and varsity athletic career at NC State, Holmes became the university’s first black graduate when he accepted his degree in electrical engineering during commencement exercises at Reynolds Coliseum on May 29, 1960. Two of Holmes’ African-American classmates graduated from NC State several years later, and the third graduated from North Carolina Central.

“Out of the 220 freshmen that entered electrical engineering with me, 65 of us graduated in four years,” says Holmes, who earned induction into engineering honor society Eta Kappa Nu as a senior. “What that proved to me was that it wasn’t color that mattered; it was intellect. That made standing on that stage that day extra special … because it proved my mom was right in thinking who I was and who I could be.”

Honoring Holmes’ enduring legacy as a student, athlete, and engineering, the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering inducted him into the inaugural class of the ECE Alumni Hall of Fame in 2015.

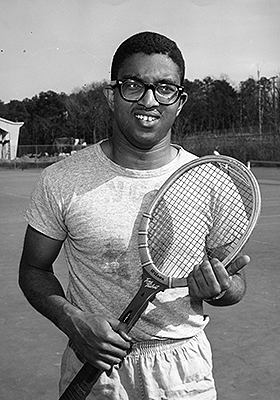

When NC State Chancellor Randy Woodson first met Irwin Holmes in 2010 at the 50th reunion of the 1960 class, he was moved by Holmes’ perseverance and dedication to overcoming obstacles and breaking new ground in both academics and athletics. Not only was Holmes the school’s first black graduate; he was also the Atlantic Coast Conference’s first black athlete, first black varsity letter winner and first black co-captain of a varsity team. Ever since that meeting, Woodson felt strongly that Holmes’ legacy needed to be honored.

In September 2018, the NC State Board of Trustees approved changing the name of University College Commons to Holmes Hall. This week, as NC State begins its celebration of Diversity Education Week, Woodson makes the name change public. The building will be formally rededicated during a celebration with Holmes and his family at 1 p.m. on Nov. 1, during Red and White Week.

“Irwin Holmes not only fulfilled his dreams at NC State; he boldly broke barriers that would forever change this university and the Atlantic Coast Conference,” Woodson says. “He was, and will always remain, a role model that helped drive needed social and cultural change at NC State, in North Carolina and far beyond.

“We are proud to honor Irwin Holmes in perpetuity with this naming.”

The three-story, 21,500-square-foot building was built in 2007. It is home to the Exploratory Studies program, Study Abroad, four classrooms and University Housing offices for Tucker, Owen, Turlington and Alexander residence halls.

It is located adjacent to Wellness and Recreation’s tennis courts at Carmichael Gym, where Holmes spent so many hours practicing and playing for the Wolfpack when the varsity tennis courts were near that location.

Last month, Woodson and Vice Chancellor for University Advancement Brian Sischo visited Holmes at his Durham home to share the news, catching Holmes a little off guard.

“I did not anticipate that they would name a building after me,” says Holmes, who is already the namesake of the Irwin Holmes and Black Alumni Society Conference Room on Centennial Campus. “I thought maybe a scholarship or something. What I appreciate is not that this is a special moment for me, but that it is a special moment for the university because a long time ago they did something special and they have been doing special things as they relate to race throughout all these years.

“By doing all of that, they earned the honor of honoring themselves.”

While Holmes spent most of his sports career as a tennis player, he and fellow African-American freshman Manuel Crockett of Raleigh’s Ligon High School actually integrated ACC athletics in a freshman indoor track meet against North Carolina in what is now known as Dorton Arena. They both ran in the 600-yard dash, becoming the first African-Americans to participate in an ACC-sponsored event.

“We didn’t perceive it to be that big a deal at the time,” Holmes says. “We were probably worried about passing a math exam or something. We thought someday when we were old men maybe someone would make a big deal about it, but we didn’t make a big deal about it.

“We did it for the same purpose as everyone else: just to have fun.”

Later that spring, Holmes joined the tennis team, while fellow African-American freshman Walter Holmes (no relation) joined the Wolfpack soccer team and the NC State marching band.

while at Hillside High School, joined the NC State team in 1957.

Irwin Holmes admits that, like most pioneers, he did not have a perfect college experience. He believes, however, that there were many honorable reactions to potentially negative events during his NC State career.

He had professors who not only helped him navigate difficult courses but also made sure he and his three other black classmates were treated fairly. One such mentor — electrical engineering professor William D. Stevenson Jr., an early developer of corporate partnerships for Research Triangle Park — recommended Holmes for his first job, with RCA in Camden, New Jersey.

Another, tennis coach John Kenfield Jr., happily welcomed Holmes, a nationally recognized junior tennis player while at Hillside High School, onto his team of all walk-ons when Holmes showed an interest in joining the freshman team in the spring of 1957.

“Coach Kenfield was a special man,” Holmes says of the Wolfpack’s tennis coach from 1949 to 1967. “He must have been raised special. He was ready for all the crazy things that happened after that.”

Many of those “crazy things” would be unfathomable in today’s world.

In his first freshman match, Holmes earned a forfeit victory because his opponent’s coach didn’t want his player to face a black opponent.

“Hey, this is great,” Holmes told Kenfield. “If they keep doing that, I’ll be undefeated.”

Throughout his career, Holmes wasn’t allowed to compete in South Carolina, which had an unwritten rule barring interracial athletic competition. All matches the Wolfpack played against the University of South Carolina and Clemson were held in North Carolina.

“Coach Kenfield arranged to have all those matches here at NC State because he said if you can’t play us with Irwin on the team, we’re not coming down there,” Holmes said. “It was upsetting to me, because like most athletes, I enjoyed traveling to different places and I never got to go to South Carolina.

“So, just to add a little salt, any time I played someone from down there, I just destroyed them.”

That sentiment of including Holmes in all team activities carried over to his teammates. Once, when coming home from a match at UNC, the team stopped for a meal at a diner outside Chapel Hill. Before serving the team, the diner’s owner told Kenfield he wouldn’t serve Holmes.

“Coach went and told the other team members,” Holmes says, “and they said, ‘If they are not going to serve Irwin, they are not going to serve any of us. We’ll get in the cars and go home.’ And that’s what they did.

“Remember, this was coming from roughly 10 white peers, all of whom had been raised in the Deep South and in traditional Southern homes. For them to feel that good about me was not a racial statement. It was them saying, ‘You are wronging our friend and therefore we are not going to participate in it.’

“That was very special to me.”

When Holmes was elected co-captain of the tennis team in 1960, he was included in Sports Illustrated’s “Faces in the Crowd” feature for becoming the first African-American captain of an ACC varsity team, a true honor for someone who spent the little money he earned selling Durham newspapers to pay for his annual subscription to the sports magazine.

Holmes went on to earn a master’s degree in electrical engineering from Drexel University in Philadelphia. He met his wife, Meredythe, an elementary school teacher with degrees in early childhood education, while he was working for RCA. During their 54-year marriage, they’ve raised three children and now have three grandchildren. Holmes had several jobs as an engineer before returning to his hometown of Durham in 1979 to work for IBM until his retirement in 1988.

Now 79, Holmes appreciates what the school is doing, less for himself than for the generations that will follow.

“Every student who comes into State is going to have some relationship with that building because of what is there, if not once but several times during their college career,” Holmes says. “That’s special.

“And it is located next to where we spent so much time playing and practicing tennis. It’s almost like that building was built just for that purpose. I know it wasn’t, but it makes this a special honor.”